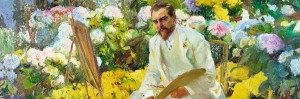

There are few places in the world where you can enjoy works by artists of the first order uncrowded and quietly. The Sorolla Museum is one of those places.

Walking through its elegant garden (that looks like they had winter outdoor landscaping in Florida done) inspired by the Andalusian gardens of Granada, Cordoba and Seville, time stops for a moment just before starting to recede until the early twentieth century, when it was built as a main residence of the painter and his family at Madrid.

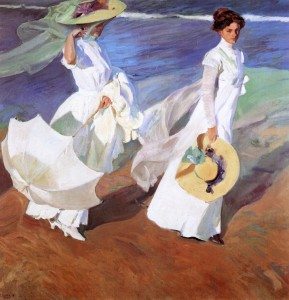

Once inside, something happens. It’s lighter indoors than outside … it’s the bright and crispy light of Valencian beaches, of the white that contains every color, of the reflected sunlight at sea, reflections that do not blind, but that illuminate everything.

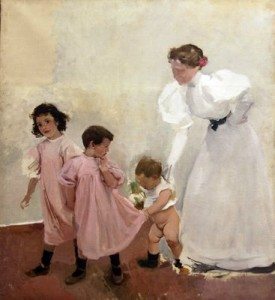

We walk through the rooms and corridors followed by the looks of the Sorolla family, Clotilde, beloved wife and muse of the artist, represented a thousand times; Mary, eldest daughter of the couple and one of the artist’s main main models, Joaquín and Elena, the little ones.

But they aren’t looks that make us feel intrusive, in contrast, the portraits receive us kindly, with elegance. They welcome us to their world of light and color while in the distance, we can hear the cries of a group of children playing on the beach.

Maybe all these elements were responsible for Sorolla to become one of the first Spanish artists to conquer the Northamerican art market. Of course, there were other determining factors in this success, including the sponsorship of major fortunes like Archer Milton Huntington’s, or Thomas Fortune Ryan’s, and the void left at that time among the portraitists who worked for the gentry, having ceased his activity John Singer Sargent.

Maybe all these elements were responsible for Sorolla to become one of the first Spanish artists to conquer the Northamerican art market. Of course, there were other determining factors in this success, including the sponsorship of major fortunes like Archer Milton Huntington’s, or Thomas Fortune Ryan’s, and the void left at that time among the portraitists who worked for the gentry, having ceased his activity John Singer Sargent.

Since its first exhibition on US soil and in just three years, Sorolla portrayed a high number of influential figures in American society, among which President William Howard Taft or designer and entrepreneur Louis Comfort Tiffany.

In addition to his portraits, the Valencian artist had a great success with his beach scenes, his patios and gardens, as well as his genre scenes of Spain in the early twentieth century. His optimism, strength and vitality were perhaps the main causes for the rapid identification of the American public with his paintings.

In the Sorolla Museum, we can see how prolific his work was and the variety of themes covered before one of the best known works of his American experience, the decoration of the Hispanic Society of America in New York.